EduTrak ePayTrak one of the best software fee collection /payment application for your school college or institutions.

Secure your network, be efficient and confident and improve your bottom line. Our one of the specialist software for fee payment, make easy for students and families to pay for all school fees, activities, services and products online. Our moto is every fee on every campus, to be collected hassle free at the end of account department and same for payee.

EduTrak payment

processing software for schools brings you a state-of-the school fee payment

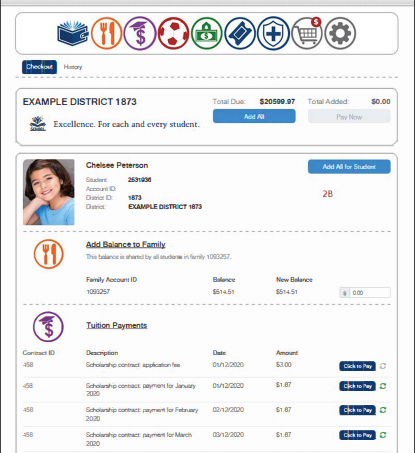

system that is fully integrated with PowerSchool! Parents can check tuition

balance and past and future payments from same login for grades and other key

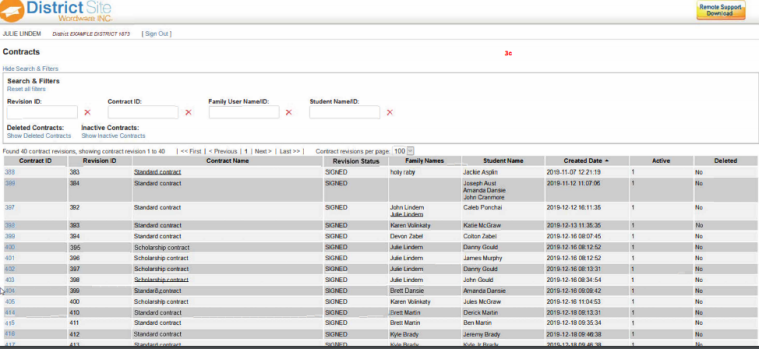

student information. Our advanced billing and contract management features are

the unique way to manage your school’s tuition payments. Administrators,

Account, staff, and parents have access to the information they need.

EduTrak Software Solution is a subsidiary of Company Advanced Payment

Technologies. We have most experienced team which have more than a decade of

expertise to development and delivery of ecommerce, school related application,

SIS, and payment software solutions. Our technology solutions (payment software

solutions) are hard at work powering improved operational efficiency, enhanced

administrative productivity and upgraded convenience at more than dozens of

schools and service institutions across North America. We have offices in Wayzata,

Minnesota and Boulder, Colorado United States of America.

Payment processing

for education ePayTrak payment software provides Every Payment Option for

Today’s Modern Schools in Technology

era-

We have online

payment solutions for school activities like Athletics and activities including

custom forms tied to the payment. EduTrak eases headache for schools

administration for Payment processing for schools, institutions,

organizations of any size and located anywhere. We have most powerful and

secured, trusted software solutions in the industry. We have integrated School fines

and fees with many SIS systems across United states. Software have option for complete

spirit wear sales and inventory tracking. Cafeteria applications also provide Food

service and collect lunch payments in a standard manner. Organizers can use our

Ticketing application for reserved seat and GA ticketing with box office and

door scanning with advanced payment collection. It has option for Affordable

fundraising. School payment solution

easily enables recurring billing for school age child care, insurance, trips,

and more. Payment collection software enables product templates for parking

permits, field trips and more. One of the best Online payment solutions for

schools is made by EduTrak Software for school payment processing and child care

payment. EduTrak online school payment system collects school fee online and

keep record of deposits and due fee.

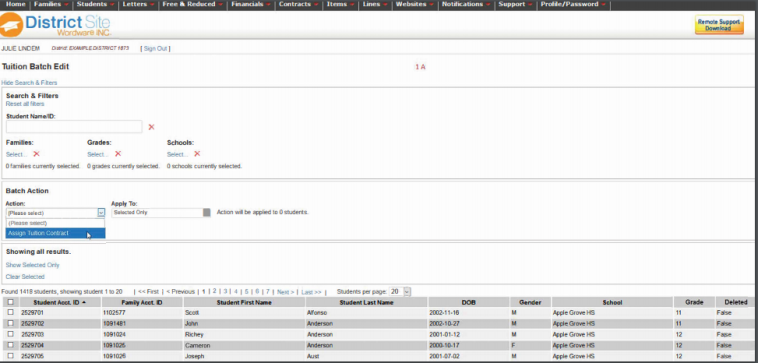

School payment solutions / school fee collection software ePayTrak Features for School Administrators – We are listing few of the features of school tuition payment systems of ePayTrak features for school administrators:

Using School fee software schools can create Custom online catalogue, create a listing of classes, services and products using various form available in the software solution.

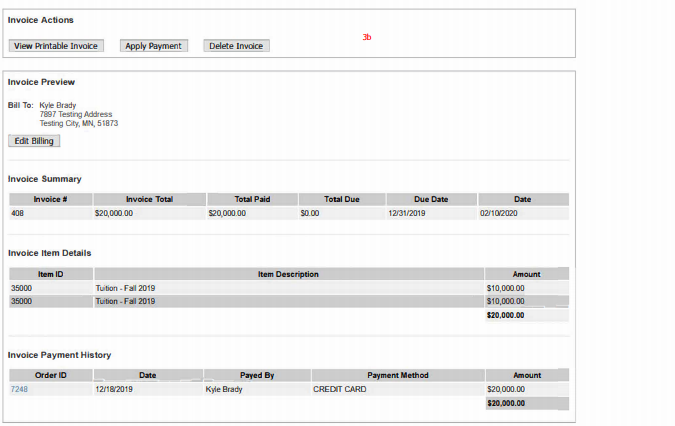

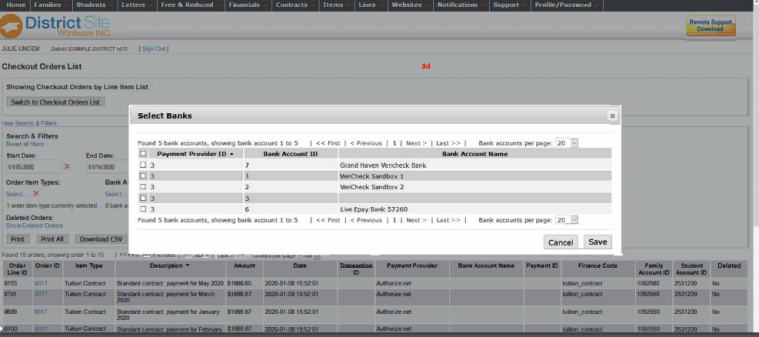

Online payment collection software allows schools administration for recurring billing schedule and generates recurring transactions based on selected data. Admin can decide for charging the same amount for every period or change the recurring amount for a selected period. EduTrak credit card software solutions allows for credit card processing for schools so that parents / guardian / customers pays organizations easily at any time.

Fee collection software enables multiple accounting attributes, Each class, fee, product, or service can be associated with multiple attributes such as account, department or budget code for tracking and reporting functionality.

- Security in your hand configurable security levels Gives school administrators a wide variety of security access and control

- Self-Branding Customized look and branding of public site –Allows you to use your school logo, colors, slogan and much more to create the look and feel that’s right for you!

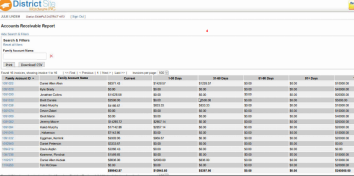

- Multiple Summary reports- Select by individual card number, department, account code, User ID, student ID, transaction, or much more

Student payment software ePayTrak Features for Families and Student

After Integrating online payments for schools families and students benefited with ePayTrak which provides flexibility and ease of use, some of the listed features are shown below-

- Setting up individual payment account – Users can set up their own accounts to make payments, pull payment reports, review scheduled transactions, and more!

- Software could be Integrated with many SIS systems – including single sign-on with those SIS systems that support it

- Software system records Transaction history – Users can easily browse past transactions with a simple click of the mouse

- Guest access browse the school’s offerings – Users can bypass the login process and browse through the site, selecting classes, services, or products to place in their shopping cart. They need to log in, or register for a new account before final purchase.

ePayTrak School fee payment / school fee collection – Features for All Users

School payment software for Schools – administrators and family/student users will benefit from the following features:

- Customize e-mail templates and receipts

- Customizable administrative security levels

- Best In class encryption

- Customized reports and e-confirmations

- Easy import/export capability

- Direct integration with many SIS systems

Edutrak is known for its secured platform for School Fee Collection. Our

platform uses the most powerful security and encryption tools available in the

industry. Edutrak is secured for your school and fees management. You can make

transactions without any worry. Our automatic payments are much safer than writing

a check. Right from maintaining student

record, fee calculation, auto-generated receipts, SMS/email reminders to

secured transactions, an online fee management system can prove to be a

game-changer for your School / Institute / Organization. EduTrak School Payment

software is one of the leading fee management software with the lowest

transaction rate that can automate the fee payment and collection procedure and

save staff members time and efforts.

Let us show you how we can help your team streamline internal processes, improve communication and collaborate better so you can focus on what you do best. Schools that uses our online fee payment module, are loving it and enjoying having everything at their fingertips and their fee management becomes easier. Our fee collection software is a complete, affordable, user-friendly software solution that is specially designed to make your task easier and stress-free. Educators looking for efficient and cost-effective software, you can opt for EduTrak complete Solution named SmartSchoolk-12 . Looking for performance, security and value? Contact Us: 1-800-365-7270 Email: info@edutrak.com